Mobility

Jacqui Belleau | Creative Director

Jacqui Belleau

In August, I had the incredible opportunity to experience weightlessness on a Zero Gravity flight. Not only was it a personal dream come true, but I gained first-hand knowledge that has shaped my perspective on how we should design for humans in microgravity environments for the next era of space exploration.

I believe people and teams designing off-world environments should join Zero-G flights to better understand the effects of microgravity to deliver more fully informed solutions.

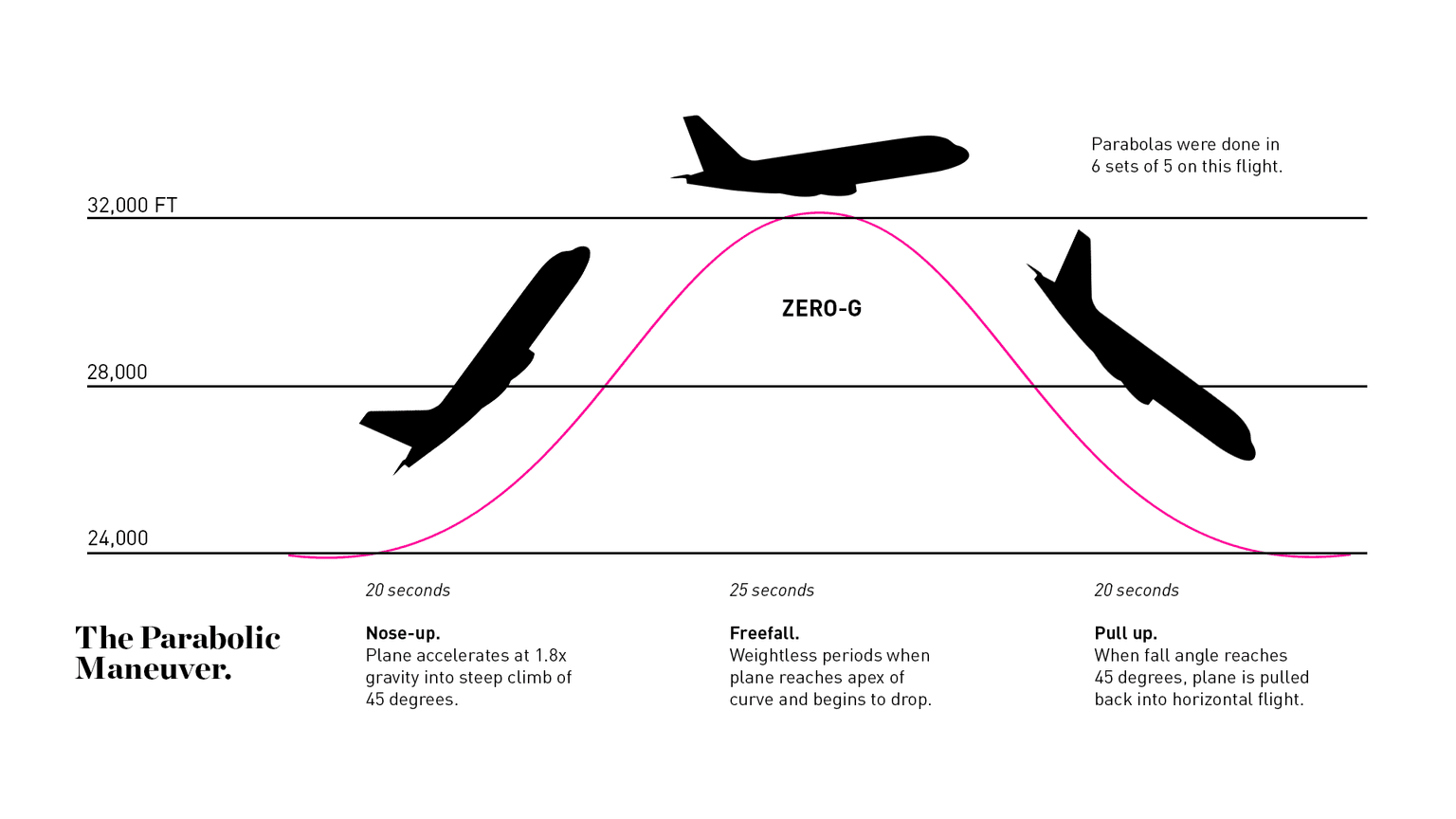

A Zero-G flight takes you through a series of parabolas, steep climbs, and descents in a converted Boeing 727 aircraft, creating a microgravity environment for 25 to 30 seconds at a time. Currently, these flights are the only way to experience weightlessness on Earth like you would in space.

Zero-G flights are critical for testing hardware designs and training future spaceflight participants. As a designer moving through 12 combined minutes of weightlessness, some of my learnings were observable, but many were experiential. Based on the breadth of these practical and emotional insights, I believe people and teams designing off-world environments should join Zero-G flights to better understand the effects of microgravity to deliver more fully informed solutions.

At Teague, we’ve designed experiences and environments in aerospace for more than 50 years. As product design consultants and experts in human-centered design (HCD), we’ve interviewed astronauts, tested designs via mock-ups, and leveraged VR and AR tools to simulate microgravity and envision future use case scenarios.

However, microgravity is not something we can relate to in a strictly Earth-bound human experience. At the same time, commercial space is broadening access to low Earth orbit and beyond for more of humankind. To enable more people to go to space and contribute to new discoveries and research, we must design microgravity habitats that are more accessible and easier to use for lesser-trained future crews.

Having access to microgravity as part of Teague’s design innovation and development process is an important tool to inform our understanding, influence design directions, and guide our recommendations for these new off-world environments.

As a first-time flier on a research flight with about 30 parabolas, it took me 10-15 parabolas to begin feeling capable in the environment. I thought I knew what to expect, but the reality of moving in microgravity was more sensitive than I imagined.

Having access to microgravity as part of Teague’s design and development process is an important tool to inform our understanding, influence design directions, and guide our recommendations for these new off-world environments.

In my first few parabolas, I was shocked to find myself shooting up and subsequently “stuck” against the ceiling. Over time, I was able to maneuver more effectively: pinching a padded panel to shift direction, lightly pushing off the ceiling to gently redirect my path towards the floor, and gliding above and under other humans in unexpected but delightful ways.

I learned which restraint and mobility aids (R&MAs) I preferred when I needed stability, and how useless my limbs were in “righting” myself. I bounced off my backside in Lunar Gravity (a fun surprise!) because I couldn’t get my feet back under me once they got ahead of my body. Through countless moments like this, I better appreciated the importance of accessible R&MAs.

I was inspired to imagine how we might design in new ways for humans in different microgravity environments. For example:

In sharing my experience, I’ve heard many interesting responses from team members across Teague, sparking ideas they’d like to explore. Imagine the knowledge base we could pull from if more designers, researchers, artists, and makers could bring their perspectives to a Zero-G flight, make new connections, and identify new possibilities!

My experience in microgravity confirmed that strong partnerships between human-centered design and engineering teams will improve the human experience in space and enable lesser-trained crews to be more comfortable, confident, and capable of achieving mission success.

Design is the bridge between the fuzzy front end of human needs and brand vision and strict engineering requirements around system performance and safety.

Previously, we would invest in extensive training for professional astronauts. Moving forward, different levels of training and more intuitive design solutions will be needed to accommodate a wider range of space explorers. With human-centered design involved in early-stage mission design and planning, designers can help save development costs and time by anticipating user needs and rapidly testing, iterating, and validating those ideas.

Design is the bridge between the fuzzy front end of human needs and brand vision and strict engineering requirements around system performance and safety. If we want more people and businesses in space, we must develop intentional experiences, interfaces, and environments that optimize for both system and human needs.

Design having a seat at the table early in commercial space development will significantly improve the experience we deliver for future crews, helping them to more efficiently contribute to new discoveries that benefit humankind and industry in space.

Designers having the opportunity to experience microgravity is a giant leap forward. When we send the first designers to space, I can only imagine the impact they will have—in bridging requirements and what’s possible—on our collective space future.

Header image courtesy of Zero-G Experience®