Space

In 1969, NASA astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin made history by taking the first human steps on another planet. Nearly 50 years later, private spaceflight companies like SpaceX, Virgin Galactic, and Blue Origin have their sights set on taking us back.

Our team has a long history with human flight. Over the last 75+ years, we’ve partnered with Boeing and airlines around the world to deliver groundbreaking airplane interiors. We've also collaborated with NASA and private space companies to improve the experience of astronauts living and working in space.

If there’s one thing we’ve learned along the way, it’s that designing for human spaceflight is an endeavor all its own.

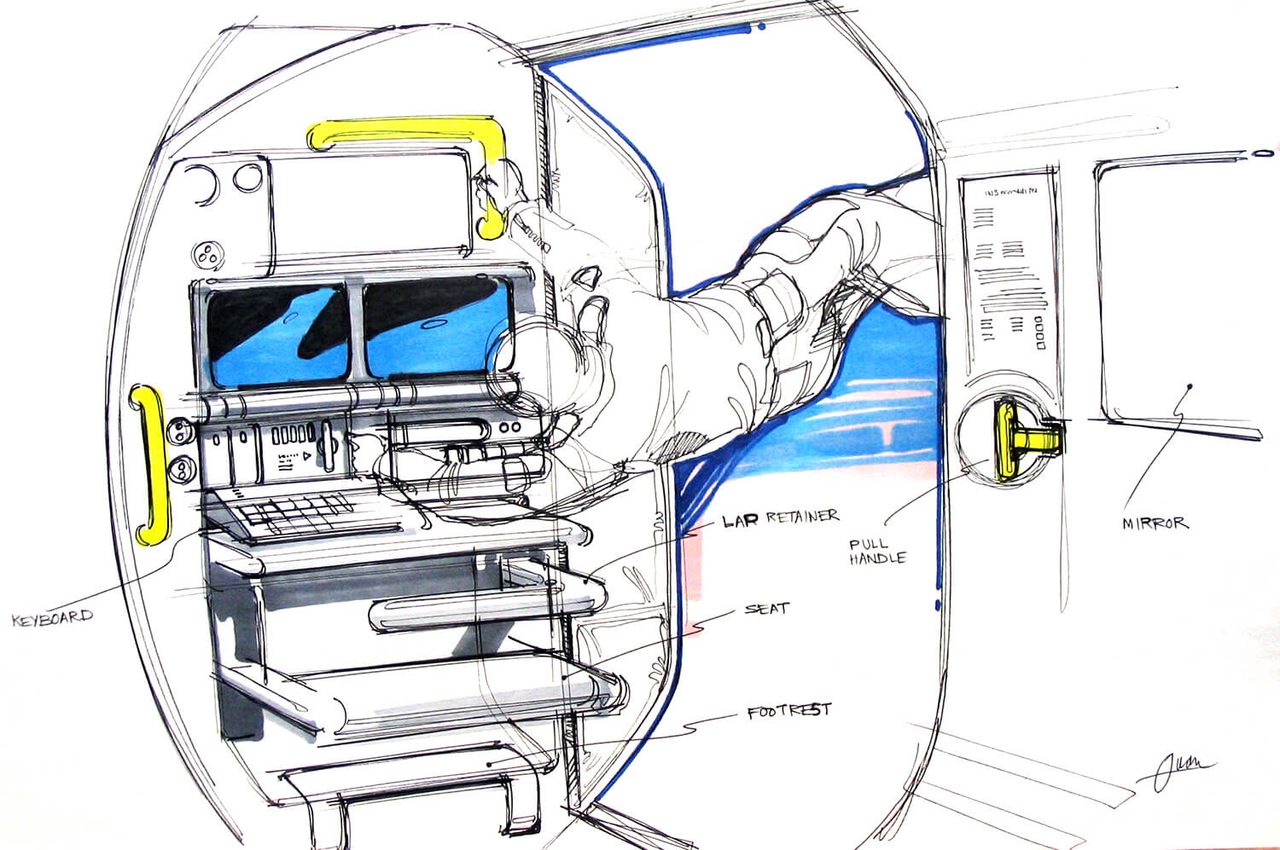

“Back in 1988, when we were tasked to work on the ISS Habitat Module, the biggest challenge was completely rethinking how we would design things differently for a near-zero gravity environment,” says Bill Quan, Senior Industrial Designer and a 33-year-veteran at Teague.

“Simple things like sleeping, workstations, stowage, the importance of exercise, and the multi-use of limited space took on new meaning. Although we had to address the functional aspects of the habitat space, we as designers were also tasked with allowing for some personalization of each crew quarter.”

Teague continues to explore designing human experiences in microgravity. How can the design of the spacecraft interior reduce the physical and psychological stresses of traveling in space? This was the challenge we posed to the University of Washington’s Industrial Design Senior Class. To add to their constraints, Teague provided the students with a physical mockup that represented the interior volume of their spacecraft.

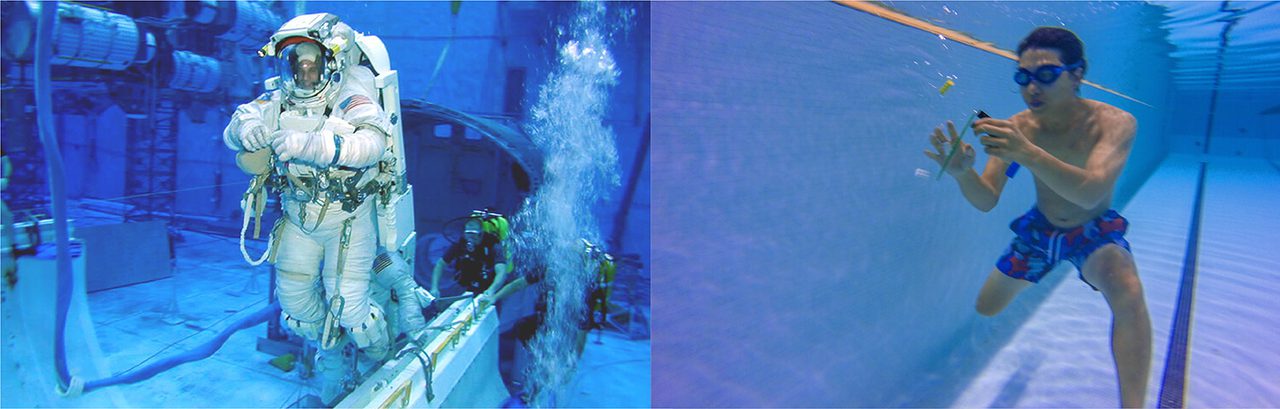

Guided by UW Professor Jason O. Germany and Teague designers Justin Lund, Karen Ng, Tara Sriram, Gary Liljebeck, and Evan Schoups, our student teams dove right in – literally! While they couldn’t get to outer space, they could get to UW’s swimming pool in the IMA Building. Being underwater provided an excellent simulation of floating in microgravity – NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Lab (NBL) uses a giant indoor pool and specialized suits to train astronauts on Earth. Working in groups of 4, they attempted everything from folding towels, to changing clothes, to building LEGO sets underwater.

“Astronauts often experience a loss of dexterity and reduced hand-eye coordination in outer space. Simple tasks like picking up objects or closing things can become quite difficult,” says Sriram. “On longer missions, their eyesight is also affected due to their eyeballs changing shape and flattening. In some ways, it’s similar to the problems the elderly face on Earth.”

The teams also conducted a series of immersion studies to experience firsthand the challenges of living in a confined space. A few groups confined themselves inside a Teague-provided mockup, where they attempted to complete an activity using LEGOs. Another team locked themselves in a small room for three hours.

“Confined spaces can be stressful, and forced socialization is tiring and awkward. There is limited access to everyday things,” noted one team in their research summary. “Long periods of isolation cause a lot of strain on a person’s mental stability, and the lack of personal space on spacecraft causes claustrophobia and makes storage quite hard,” observed another.

Author Mary Roach described it best in her book, Packing for Mars: Human beings are “the most irritating piece of machinery (rocket scientists) will ever have to deal with.” To artists and designers, however, humans are the most intriguing part of the problem. Through their own studies and primary/secondary research sources, our UW students started to identify what they saw as the key pain points of space travel that would be addressed through design:

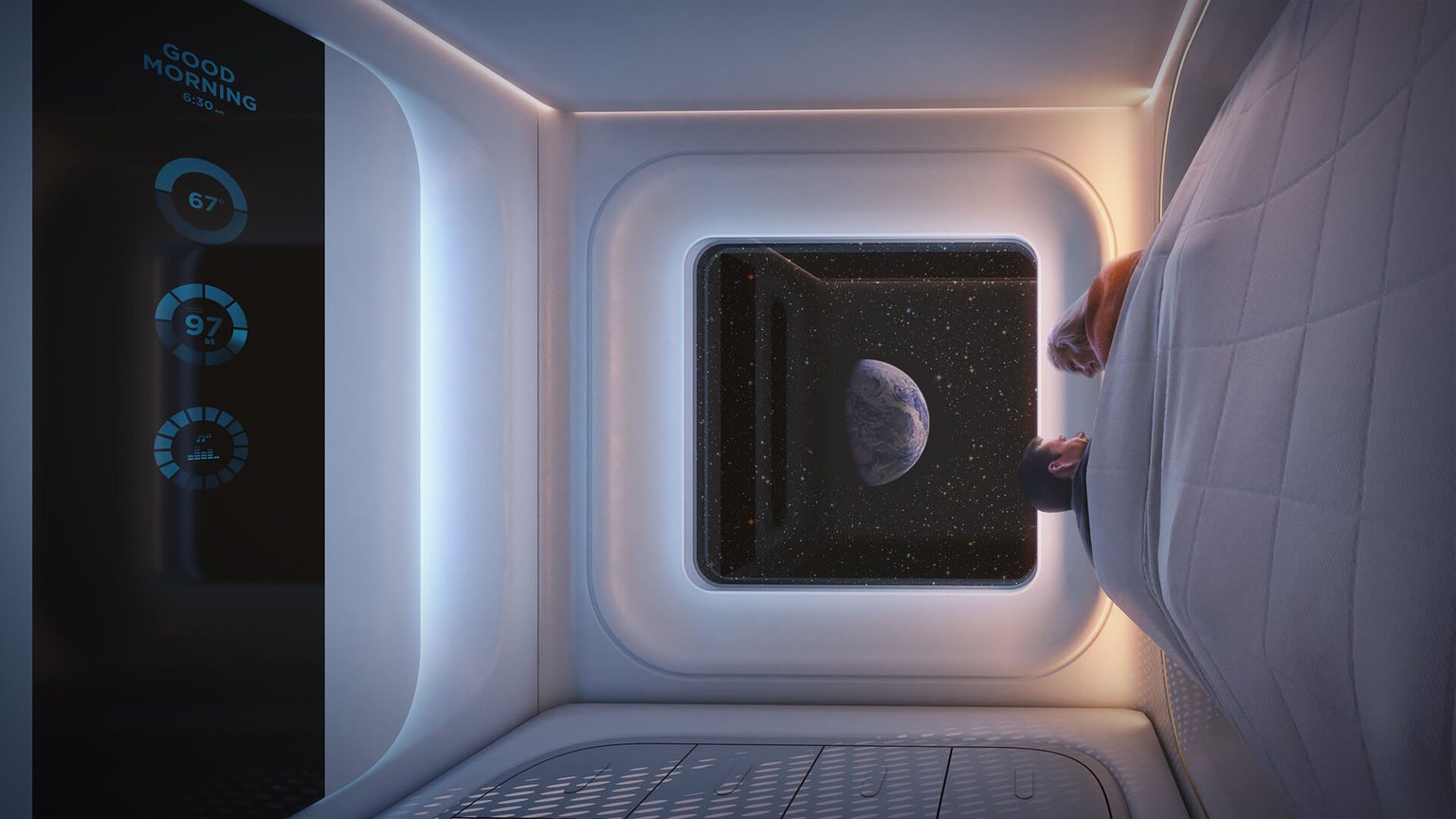

Natural light, or the lack thereof, is another factor that affects physical and mental comfort. “Humans have a 24-hour natural biological cycle, called a circadian rhythm, that needs to be reset every day. There are photoreceptors in the eye fully dedicated to registering a small range of wavelengths of blue light that trigger the resetting process,” says Evan Schoups, Senior Systems Designer and lighting expert. “In space, where your light exposure does not depend on the sun rising and setting, the danger of falling out of sync is very real and can be detrimental to a person’s health and well-being.”

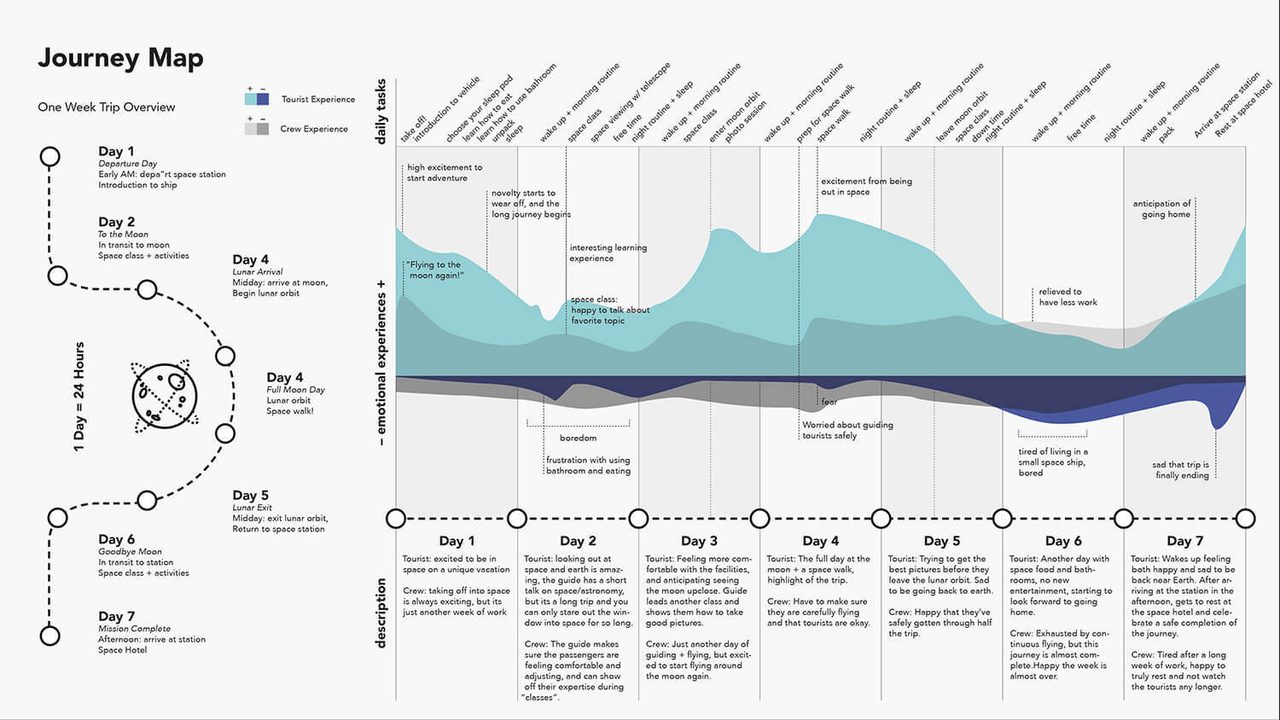

Once considerations were flushed out, the UW students next generated interior concepts that could create an idealized experience and alleviate these pain points. A key part of this process was developing a journey map to better understand and empathize with what a space tourist might experience in this strange new environment. Teague experience designers and UW ID alumni Bernadette Berger and Emily Pasternack facilitated a workshop to guide them through this process.

“Journey mapping is an important part of understanding the axis of time. How do traveler needs and expectations change throughout a day, an entire trip?” says Berger. “By uncovering passengers’ changing needs, the students were then able to create physical objects, digital interfaces, and architectural spaces, which could weave together an evolving experience. These experiences sought to influence passenger perception, behavior and interactions, as the thrill of flight waned and the longing for home grew.”

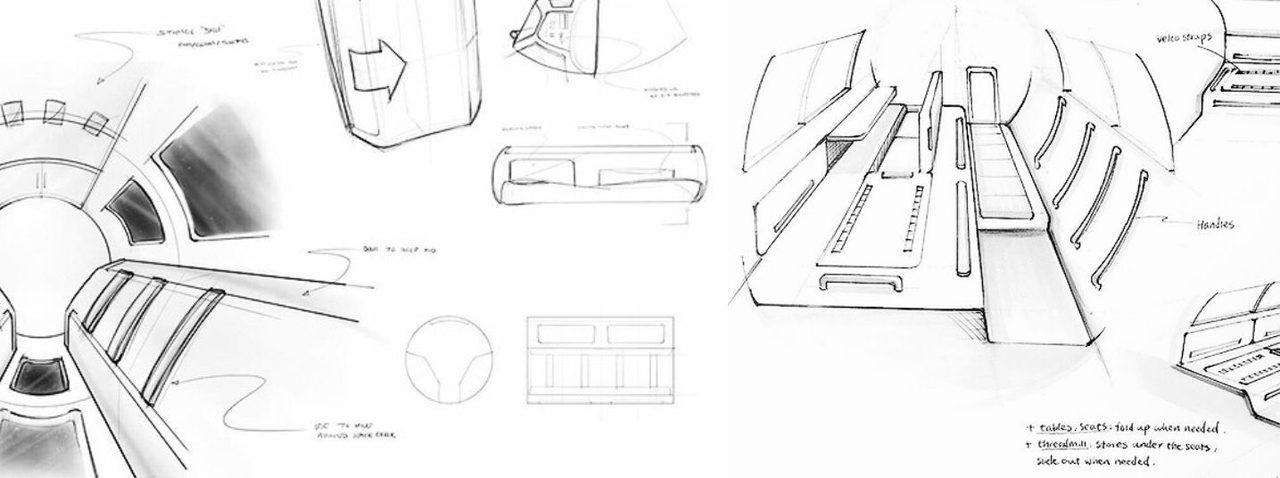

The UW designers quickly realized there was a need to separate a communal public space from individual personal zones. Maintaining a healthy social dynamic between passengers was a large part of the problem – and sometimes, you just need some alone time after a long day of extraterrestrial activities.

Our teams also had to deal with designing inside a tube – like airplanes, space capsules need to be pressurized, which drives them to round or spherical shapes. ‘Thinking through making’ is the core of Teague’s design ethos, and the groups were encouraged to develop their concepts three-dimensionally through scale models and 1:1 scale foam core mockups.

Final projects explored these ideas in greater detail, and ranged from concepts for cushioned sleeping pods to augmented reality window displays. Collaborating with the UW ID students was extremely rewarding: We proposed a complex design problem and got to witness their process of discovery and insight. The project culminated in an open house and presentation to the larger Teague studio, and the students’ fresh perspectives and professional presentation truly impressed us.

As space tourism moves from science fiction to reality, human-centered design will play a critical role in shaping our future extraterrestrial experiences.

“By focusing on commercial space travel, this studio acted as an extremely unique platform for students to explore the implications that design can have on the future of mobility,” says Professor Jason O. Germany. “This level of exploration couldn’t have been possible without a partner like Teague and their expert design team, which was critical to the success of this project and a means of connecting coursework to professional practice.”

The uncharted territory of space travel is an exciting opportunity for designers, both student and professional. As space tourism moves from science fiction to reality, human-centered design will play a critical role in shaping our future extraterrestrial experiences.

Carl Sagan said it best – “We began as wanderers, and we are wanderers still.” When humans look up at the night sky, we can’t help but think, “We’re going to go back there.” It’s quite literally a moonshot – but we’re going to try anyway.