Defense

Matt McElvogue | Vice President, Design

Matt McElvogue

Matt tackles user experience problems at the source and finds creative solutions through forward-thinking strategy, ideation, and creative direction.

Faced with the unknown, distrust of technological disruption is a natural response. History is full of skepticism toward transformative innovations. In the 1860s, when the first automobiles appeared on British roads, lawmakers didn't just set a speed limit of 2mph; they required a person to walk ahead waving a red flag. This reaction from society to disruption and our instinct to regulate what we don’t yet understand recurs with every major technological leap, from steam engines to smartphones.

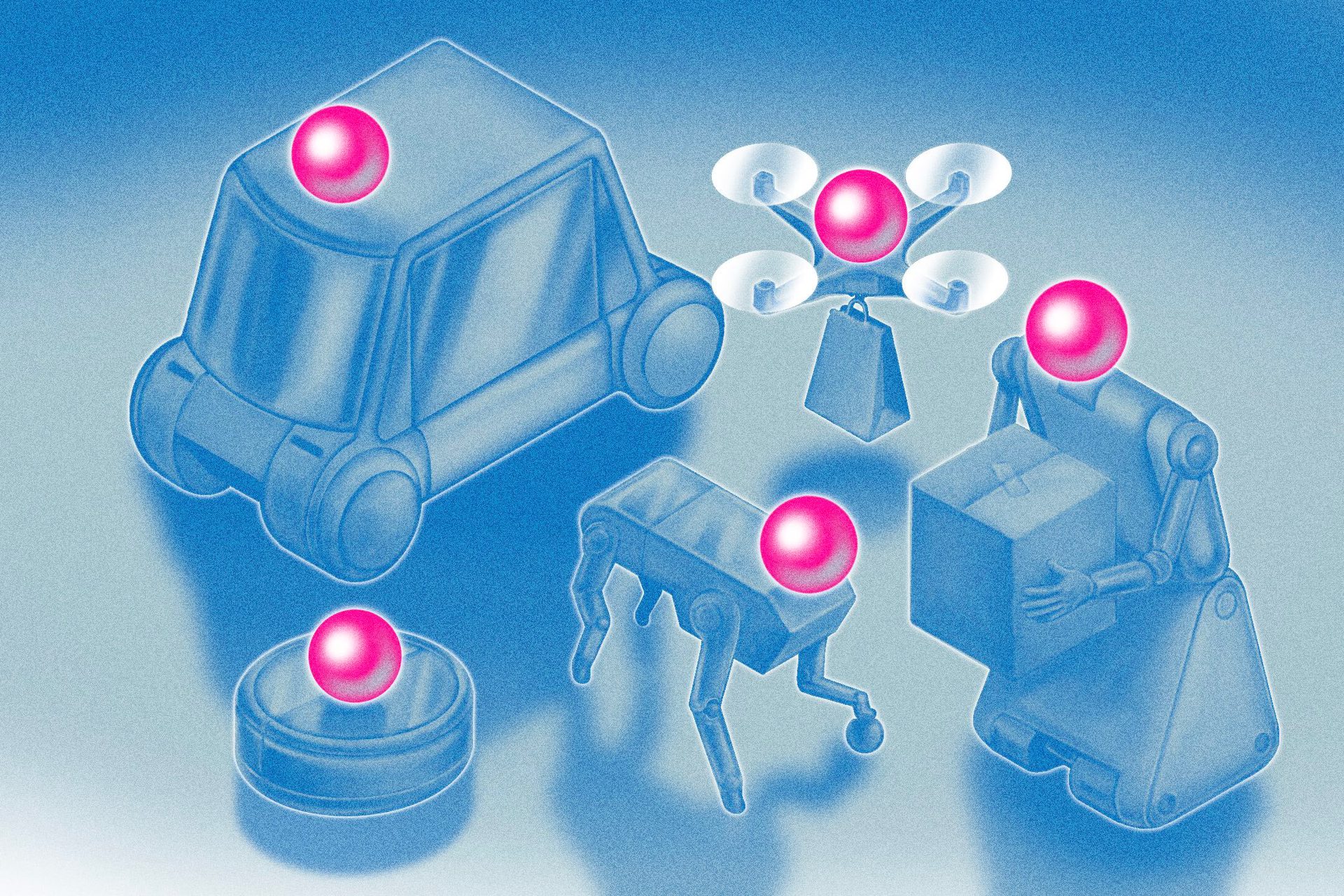

Today, humanoid robots like Tesla's Optimus and Boston Dynamics' Atlas are moving closer to real-world deployment, with companies aiming to bring them into the workplace—and eventually our homes. While they’re not household fixtures just yet, the long-term vision is quickly taking shape, resulting in the same familiar tension between innovation and apprehension towards the unfamiliar.

These aren’t minor upgrades to how we live and work. They’re full-scale shifts in human-machine interaction, arriving faster than we can emotionally or cognitively adapt. But here’s the critical insight: user distrust often points to unaddressed design gaps.

Among emerging technologies, humanoid robots have one of the steepest uphill climbs when it comes to earning trust. Unlike other machines, they carry the burden of resemblance—looking almost human, but not quite. The uncanny valley, that psychological discomfort we feel when something looks a little too lifelike without being convincingly so, is very real. The humanoid design of today’s robots inspires curiosity, but also an undeniable eeriness.

Robots are also difficult to read. Humans are experts at interpreting intent through tone, body language, and social cues. Robots, powered by AI and wrapped in metal casings, give us none of that. Without transparent signaling about what they’re perceiving or why they’re acting, they can feel unpredictable and even threatening.

The humanoid design of today’s robots inspires curiosity, but also an undeniable eeriness.

Physical presence adds to the intimidation. Many robots are large, heavy, and powerful. When something that strong moves near a human without obvious intention or communication, fear is a rational reaction. We don’t know how to interact with them, especially when they're in workspaces or homes - environments traditionally dominated and inhabited solely by humans.

Compounding this is a deeper psychological discomfort: perceived obsolescence. When robots operate in roles historically held by people, it can feel not just like automation, but like replacement. The fear isn’t only “Will this robot hurt me?” It’s also, “Will this robot replace me?”

That’s the perennial challenge of all new tech: lack of shared experience. When people don’t have a frame of reference for how something works or what it feels like to use, it takes much longer to normalize. Without access, experience, or understanding, a trust gap naturally emerges.

If we want to bring robotics into the mainstream and our streets, homes, and workplaces then we must design for trust. It isn’t an afterthought; it must be a central pillar from day one, evolving as we introduce new technology.

Through our work in robotics, AI, and autonomy, we've identified three essential ingredients for designing trust into autonomous systems: Safety, Confidence, and Control.