Aviation

Devin Liddell | Principal Futurist

Devin Liddell

Devin designs preferred futures in aviation, automotive, smart cities, personal mobility, space travel, and more.

Connect with Devin on LinkedIn

Here's a giant red flag: Inflight connectivity is now more frequently described as a new “cost of doing business.” This is terrible news for airlines. First, the airline industry definitely doesn’t need any more costs; the average airline’s profit margin is just 0.1% and more costs won’t move this in the right direction. Second, a “cost of doing business” is another way of saying “requirement” and code for “commodity.” These are also things that airlines don’t need any more of, because airlines have already let themselves become far too commoditized already. Put simply, airlines need more ways to stand apart from each other—not more ways to be exactly the same. Unfortunately, this is the path airlines are taking with connectivity, falling into the same commoditization trap wherein connectivity on one carrier is generally indistinguishable from connectivity on another. In fact, the website for one of the leading connectivity providers—which itself has a very vibrant brand—references that it is the “exclusive provider” of connectivity to ten different airline brands, all of them operating in the North American market. The current number of equipped aircraft might be different, but the connectivity offering itself is mostly the same across any of these carriers. That’s a lost opportunity for all of those carriers. Given this, the industry then soothes itself with the idea of “monetizing” the service by retailing to its “captive audience.” This idea of ancillary revenues saving airlines from the perils of commoditization is increasingly pervasive. But it’s a fantasy. Already, there is an inverse relationship between an airline’s emphasis on ancillary revenues and its passenger preference ranking. For example, of the ten largest airlines in the world by revenue last year, three of them boast a top-20 Skytrax ranking for passenger preference, while the other seven are well outside the top 20 in passenger preference. Ancillary revenue as a percentage of total revenue averages just 1.5% among the high revenue/high preference group. The high revenue/low preference group’s average? 10%. The short version of this data: the more you depend on ancillary revenues, the less passengers prefer you. So the real cost of making ancillary revenues a bigger portion of your income is your brand. That’s not a good transaction.

Airlines need more ways to stand apart from each other—not more ways to be exactly the same.

Yet there are those who believe passengers are just panting to buy sporting, theater, and concert tickets while onboard. Or buy clothing and other products from retailers. But given that the current “take rate” for onboard Wi-Fi (the percentage of passengers who pay for a connection) is just 6%, how many passengers are really that eager to go on an online spending spree at 30,000 feet? Even if they do want to buy stuff, why not buy it before or after the flight? What problem—beyond procrastination—is inflight retailing really solving for passengers? Remember: one of the fallacies at the heart of the dot.com bubble was the notion that because you could buy something in your pajamas meant you would. As it turned out, not so much. The same thing is happening here. And it’s likely that the real problem inflight retailing is hoping to solve has nothing to do with what passengers actually want and everything do with an airline’s need for more revenue. That alone is good reason to suggest it will not be successful.

If an airline values its brand, and actively wants to create a passenger experience—in any class—that inspires passenger preference (and, thus, deserves premium pricing), it should abandon the industry’s current trajectory of me-to connectivity offerings and, instead, take two bold steps forward: create something from inflight connectivity that’s representative of its unique brand, and then give it away for free.

One of the earliest and most ubiquitous applications of inflight connectivity is the moving map, which lets passengers track the progress of their flight. While the map remains one of the most popular IFE features, this is not complimentary to the flying experience. (It’s equivalent inside a hotel room would be a “countdown to checkout” clock that guests enjoyed looking at.) Still, the moving map created early context for inflight connectivity’s emphasis on entertainment. This has now expanded to include productivity—offering Wi-Fi to business travelers so they can connect with people and data on the ground, and service—giving pilots and flight attendants more sophisticated tools for managing the needs of the aircraft and its passengers. But there’s another opportunity area airlines should consider even more when designing their inflight connectivity offering: connecting passengers to the next phase in their journey—specifically, hotels.

Inflight connectivity platforms should be built around real passenger needs and desires, both functional and emotional.

Inflight connectivity platforms should be built around real passenger needs and desires, both functional and emotional, that the airline is well-positioned to solve. Most airlines are not experts in retailing. They are not experts in entertainment, either. So, at best, most airlines can be proxies for retail and entertainment partners, which is fine, but there’s very little benefit to the airline brand. However, while airlines aren’t Amazon or Netflix, they are travel experts. They are also natural design partners with hotels, with both serving travelers and designing for confined spaces. Fueled by inflight connectivity, airlines and hotels have an opportunity to create something truly transformative together.

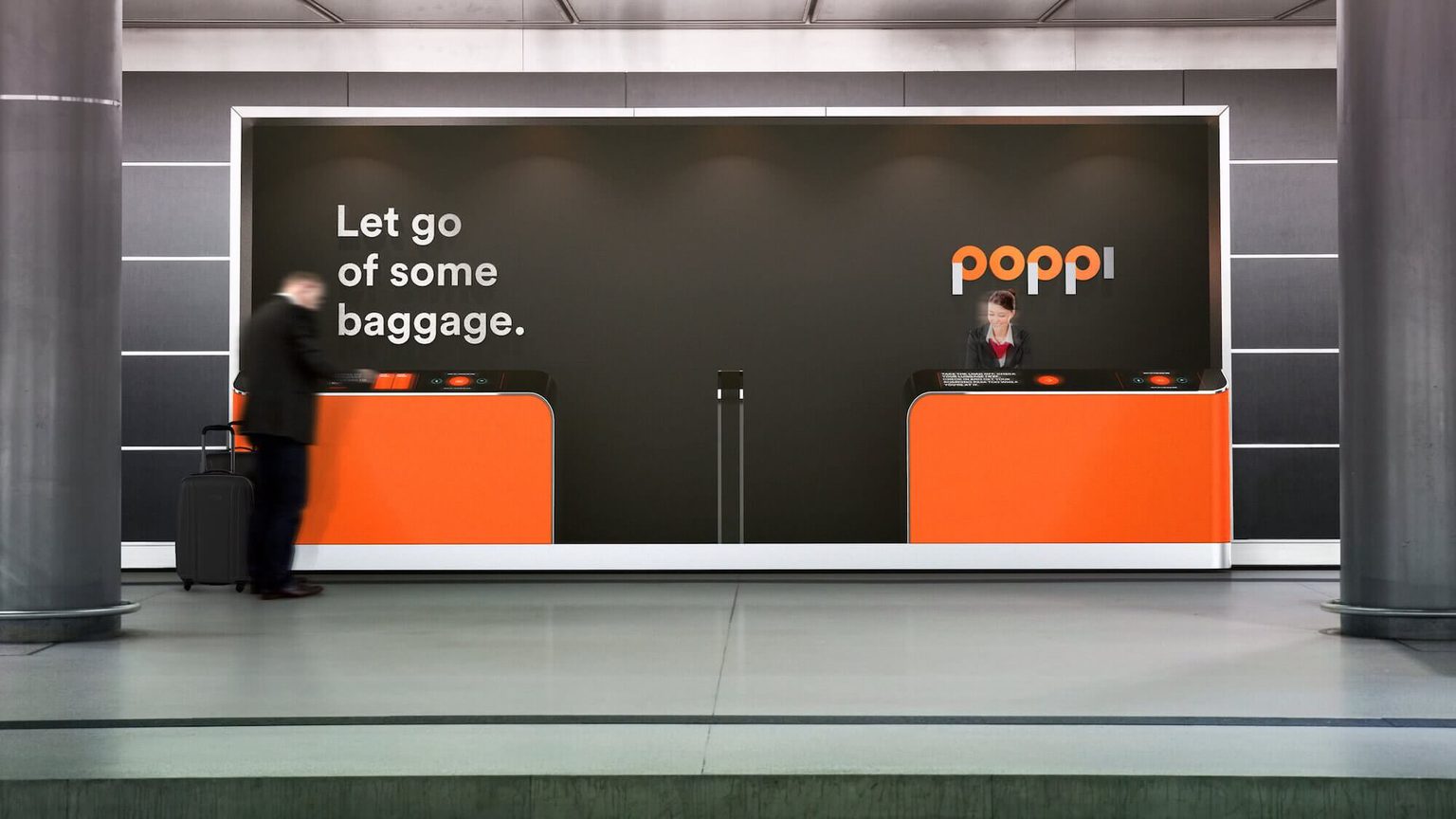

Imagine this scenario: a flight is set to arrive around 9:00pm, just an hour or so before most hotel room service and on-property dining kitchens close. So, after watching a new release movie, a passenger uses an airline’s custom app onboard to check-in to the hotel (since arrival is now imminent), which sends a digital room key to her smartphone so she can skip the front desk altogether. Then, the passenger uses that same app to schedule a room service order to be delivered just after she arrives at the hotel. But she’s not done yet. She also uses the app to optimize the temperature in her hotel room, thanks to the networked thermostat that interfaces with the airline’s custom app. Because all of this is only possible because of the airline’s special partnership with the hotel, these services are only possible onboard its aircraft. This is anti-commoditization. This is about inspiring real loyalty—not the kind of loyalty traded in points and miles and rewards. This is about doing more—and doing more differently—to create passenger preference and command premium pricing versus the competition, which are the primary reasons to build a brand in the first place. And this is just one scenario within an expansive set of possibilities for airlines to use inflight connectivity in a way that goes beyond the idea of just distracting passengers or selling stuff to them. That’s more of what this industry needs, and it isn’t even anything airlines would need to charge passengers to use, because the resulting passenger preference and premium pricing will do more for bottom lines than selling stuff to “captive audiences” ever will.

This article was originally published in Aircraft Interiors International magazine.