Technology

Devin Liddell & Sheng-Hung Lee

Devin Liddell

Principal Futurist

Sheng-Hung Lee

MIT Ph.D. Researcher

Most of us want to remain in our existing homes as we grow older. The practice of “aging in place” aligns with preferences for familiar places and routines and preserves our sense of independence. These preferences, though, raise questions about what support seniors want and need in their current homes. Japan has advanced the use of robotics specifically for this purpose, with mixed results. Despite these early results, the continued development of robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) to assist those aging in place seems obvious. What’s less obvious is how seniors foresee AI and robots living alongside them and what specifically they envision these things doing.

To better understand how seniors want AIs and robots to help in their homes, we asked them. We recruited seniors from the MIT AgeLab’s research cohort, each around 70 years in age and in the early stages of retirement, and then engaged in wide-ranging conversations about their aspirations and fears about these technologies.

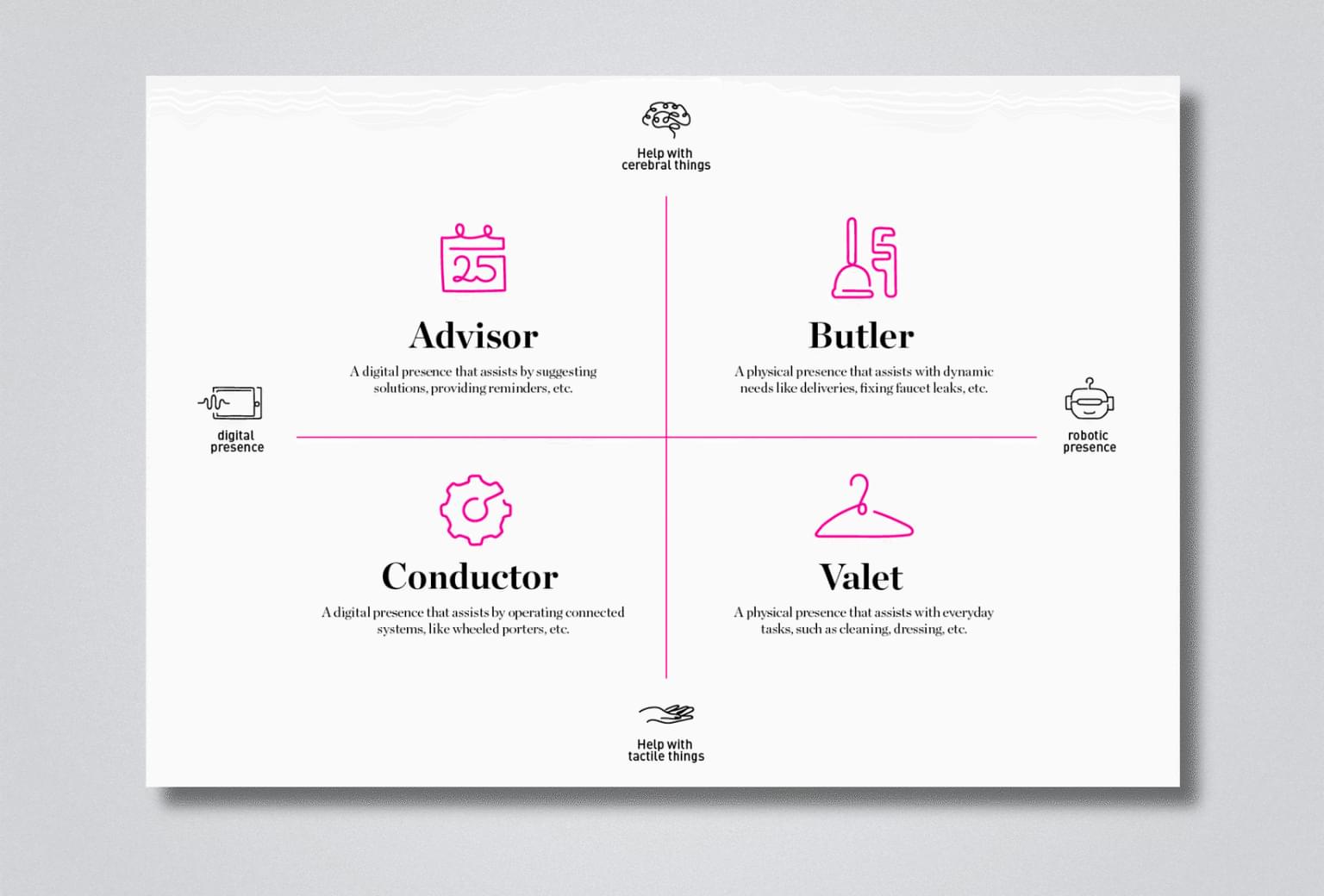

During these conversations, we explored various forms of both digital and physical AI, everything from digital assistants to handy robots, each with different capabilities and limitations. The result: here are four types of AIs in the future lives of seniors at home, along with what present-day seniors think of them and the key considerations we’ll need to account for when designing them.

A digital presence that suggests solutions to problems, surfaces opportunities, and helps its person remember to do things. Examples: the AI helps verify the veracity of an unfamiliar communications like scam phone calls; identifies activities of interest and assists in planning how to participate; offers timely reminders to take medications, and prompts calls to friends and family members on their birthdays.

What seniors think:

Thanks to established assistants like Amazon’s Alexa and Apple’s Siri, seniors say they’re already familiar with this form of AI, both inside and outside their homes, and can easily anticipate its further evolution. Moving forward, though, seniors want more from the Advisor archetype. They want the Advisor to go beyond pragmatic help with reminders about daily life and grow into helping them with their social well-being. This will mean providing actionable support with emotional concerns, especially social isolation, by surfacing and facilitating a senior’s human connections.

A physical presence that attends to its person by assisting with dynamic needs, such as deliveries, health and home monitoring. Examples: the AI robot lifts a delivery from the porch to the foyer; assists in turning off the water at the source of a leak in the kitchen; renders assistance—and summons help, if needed—in the event of a fall.

What seniors think:

Due to the confluence of connected personal devices like smartwatches and earbuds with connected home devices such as smart thermostats and automated lighting, seniors believe there are increasingly complex interactions between their bodies and their homes. So, they see how an AI robot helping to manage these complexities could reduce their cognitive load. They also acknowledge, though, that this form of AI in the home is far from simple in its creation and requires a lot of features and expansive capabilities. Just like a human butler, here there’s a distinct possibility of robots just for rich people, which will require breakthroughs in manufacturability and new business models to avoid.

A digital presence that operates connected systems of modules such as wheeled porters and object lifters. Examples: the AI responds to voice commands to transport meals from the kitchen to the living room with a wheeled porter; elevates an adjustable-height table adjacent to the dryer to ease folding clothes; summons an autonomous vacuum to address a spill.

What seniors think:

This is a challenging archetype for seniors to conceptualize in their homes since it exists the farthest away from any present-day solutions. Nonetheless, they’re compelled by the prospect of an overarching, digital administrator of a set of modular, task-driven devices. Perhaps because it’s the least familiar to them in terms of having existing corollaries, seniors are less confident in speculative interactions with this archetype because an AI with a lot of control must earn a lot of trust. At the same time, they see this form of AI as capable of adapting to their changing physical needs as they age simply through the addition of new connected devices. This will mean creating sets of modules that can be added and subtracted, potentially through subscription models.

A physical presence that attends to its person by helping with everyday tasks, such as cleaning, dressing, and grooming. Examples: the AI robot replaces a light bulb in high-ceiling recessed lighting; helps a person put on their socks and pants; cleans everyday surfaces such as kitchen and bath countertops, and dusts bookshelves and framed prints.

What seniors think:

Seniors equate the possibilities of this form of AI in the home with early home robots such as iRobot’s Roomba vacuum. While the focus of this archetype is on “everyday” tasks that include common housecleaning (vs. the “dynamic” tasks of the Butler Robot AI archetype), it also includes help with everyday personal tasks like dressing and grooming. Interestingly, here seniors have some concerns about this form of AI helping in ways that bring it into physical contact with their bodies. This will require forms of this AI that are aesthetically compatible with seniors for such personal interactions.

This article was originally published in Fast Company.