Insights

Devin Liddell & Eric Spiegelman

Devin Liddell

Principal Futurist

Eric Spiegelman

President

The taxibots are coming. GM and Lyft are using different words to describe them, saying that they’ll partner to make an “integrated network of on-demand autonomous vehicles part of people’s daily lives.” But that’s just the long way of saying “Johnny Cabs.” (You know, from Total Recall.)

So whether we want to call them taxibots, robot cabs, or the inevitable brand names that will follow, technology companies and automakers are already hard at work right now solving the design and engineering challenges required to make them a reality.

This work is essential, but there’s plenty of other important work that has nothing to do with lasers, sensors, user interfaces, or 3-D maps, and everything to do with the strategic choices individual cities will need to make for themselves. What’s right for Paris may not be right for Peoria, so every city should be preparing now to answer two important questions about the type of taxibot network it wants for its specific future.

For Profit Vs. For the People

How a city answers this question expresses what it believes–at a philosophical level–it should be providing to all citizens. Most cities in the developed world have evolved to provide–or at least manage the provision of–everything from water and electricity to mass transit and garbage collection. But why these services and not others, like Internet connectivity? Are citizens better served by industry?

Maybe, maybe not. In big brush strokes, industry wants customers that it can serve most efficiently and most profitably, which is why rural communities are far less likely to have broadband connectivity than their urban counterparts. In similarly big brush strokes, cities tend to think about the services they provide in more egalitarian terms, which is why all neighborhoods get stop signs—not just the wealthy ones. This difference, between industries and cities, will inform the design and operation of entirely different taxibot networks.

The city must own and operate its own taxibot network, rather than simply taxing and regulating an industry-run network.

So if a city believes that all of its citizens deserve equal access to transportation—including citizens at the edges of its geographic limits, citizens with disabilities, and other people who will be less convenient for industry to serve—then we believe the answer to this question of ownership is clear: The city must own and operate its own taxibot network, rather than simply taxing and regulating an industry-run network.

But what “ownership” of a taxibot network actually means is potentially confusing. That’s because a taxibot network will consist of at least three core components: 1) the taxibot fleets; 2) a physical infrastructure that allows the taxibots to communicate with the city, like an elaborate network of Wi-Fi routers; and 3) a set of operating systems and protocols that allows the taxibots to communicate with each other, as well as with other cars on the road.

Who will own the taxibot fleets is an open question. It could be a selection of small companies, as is currently the case in many American cities, or it could be that one company is granted an exclusive citywide taxibot license. Or, the city itself might choose to own the local fleet. Regardless, the access points for vehicle-to-infrastructure communication will have to be owned and controlled by the city. And the city will have to have profound influence over the protocols that govern that communication as well as the vehicle-to-vehicle communication.

This will push the city outside of its comfort zone. In the same way that carmakers will have to become software companies–or become merely hardware manufacturers for technology companies–cities will have to do the same, or become merely “street providers” to industry-run taxibot networks. This evolution will be essential to the city’s ability to provide equal access to transportation, and to align the interests of cities and citizens with the desires of carmakers and their shareholders.

Optimization Vs. Monetization

Every taxibot will be a node on a network, producing all sorts of data. This data will be valuable for the same reasons that any kind of consumer data is valuable: It can be used to improve products and services (which is a good thing) and market things to people that they may not need (which is a bad thing). At a high level, we believe a city that owns its own taxibot network will also own the data generated by the network on behalf of citizens for the purposes of continuously optimizing network performance and integrating with other city-run services. In this scenario, a city owns the taxibot-generated data, and policies governing its use are managed by the city.

There is already no future for the anonymous use of public transportation.

Either way, we believe there is already no future for the anonymous use of public transportation, a future already signaled by the rise of cashless fare payments. This will be upsetting for many, but the emergence of taxibot networks will finalize the end of anonymous use, forcing the city to engage in the legal and moral complexities of data ownership and understand how it will—and will not—use taxibot passenger data. Industry has been grappling with personal data and privacy issues for a long time now, as have many cities. But others will need to begin working through these complexities now to catch up.

These questions about who should own a city’s taxibot network and the data it generates sound like potentially dull governmental policy matters. They are definitely not. Different answers to these questions create starkly different futures that work very differently for citizens. They even look starkly different. Consider that Los Angeles could support a million two-seat taxibots by 2040. Now imagine all of those taxibots are owned by an entity or entities other than the city itself; that’s a million branded vehicles occupying city streets.

In a straightforward evolution of the illuminated placard adverts atop cabs today, maybe these future taxibots are even displaying high-definition video adverts continuously. Their cameras are tracking the eyeballs of passengers and passersby alike, serving up targeted promotions and urging pedestrians to ride rather than walk. Okay, so perhaps we’re making that scenario more nefarious than it needs to be. But now imagine those million taxibots are owned by the city. The city wants its taxibots to reflect and celebrate the city—in the same way its bridges and boulevards do. So while these taxibots are driving citizens from point to point, the mirrored finish of the city’s taxibots might literally reflect the city’s river walks and sunsets—a quiet and aesthetically cohesive transportation network that almost disappears while in use, beautifully complementing urban infrastructure rather than competing with it. Those mirrored-finish exteriors might even be networked canvases for public artists, turning freeways into moving, digital art installations.

It’s unlikely that citizens will be better served by an industry-run network of taxibots primarily motivated by profit than they’ll be by city-run networks primarily motivated to serve all citizens equally.

These opposing visions point to unreconciled tensions about the future of cities, who’s really running them—governments or corporations, and what citizens want from them. Public art isn’t better just because it’s art, and the mere presence of advertising does not make a dystopia. After all, there are already plenty of print ads on public transportation as well, not just cabs. That said, no one saw the advertising blimp in Blade Runner and said, “Wow, I can’t wait until one of those is hovering over my house.” And yet advertising is not the problem. Advertising is just a potent indicator of interests beyond the citizen. The inevitable presence of those interests is why we believe it’s unlikely that citizens will be better served by an industry-run network of taxibots primarily motivated by profit than they’ll be by city-run networks primarily motivated to serve all citizens equally. So there, we said it.

There’s a maxim shared by futurists that states we tend to overestimate what will happen in 50 years (see: flying cars), and underestimate what will have in five years (see: pre-Internet 1990s). Taxibots sound like they’re part of a far-off future. But remember that GM and Lyft have already announced their half-billion-dollar partnership to create them. And there will be more partnerships focused on taxibot futures as well, with Uber’s massive capitalization especially well-positioned to transition from “Everyone’s Private Driver” to “Everyone’s Private Robot Driver.”

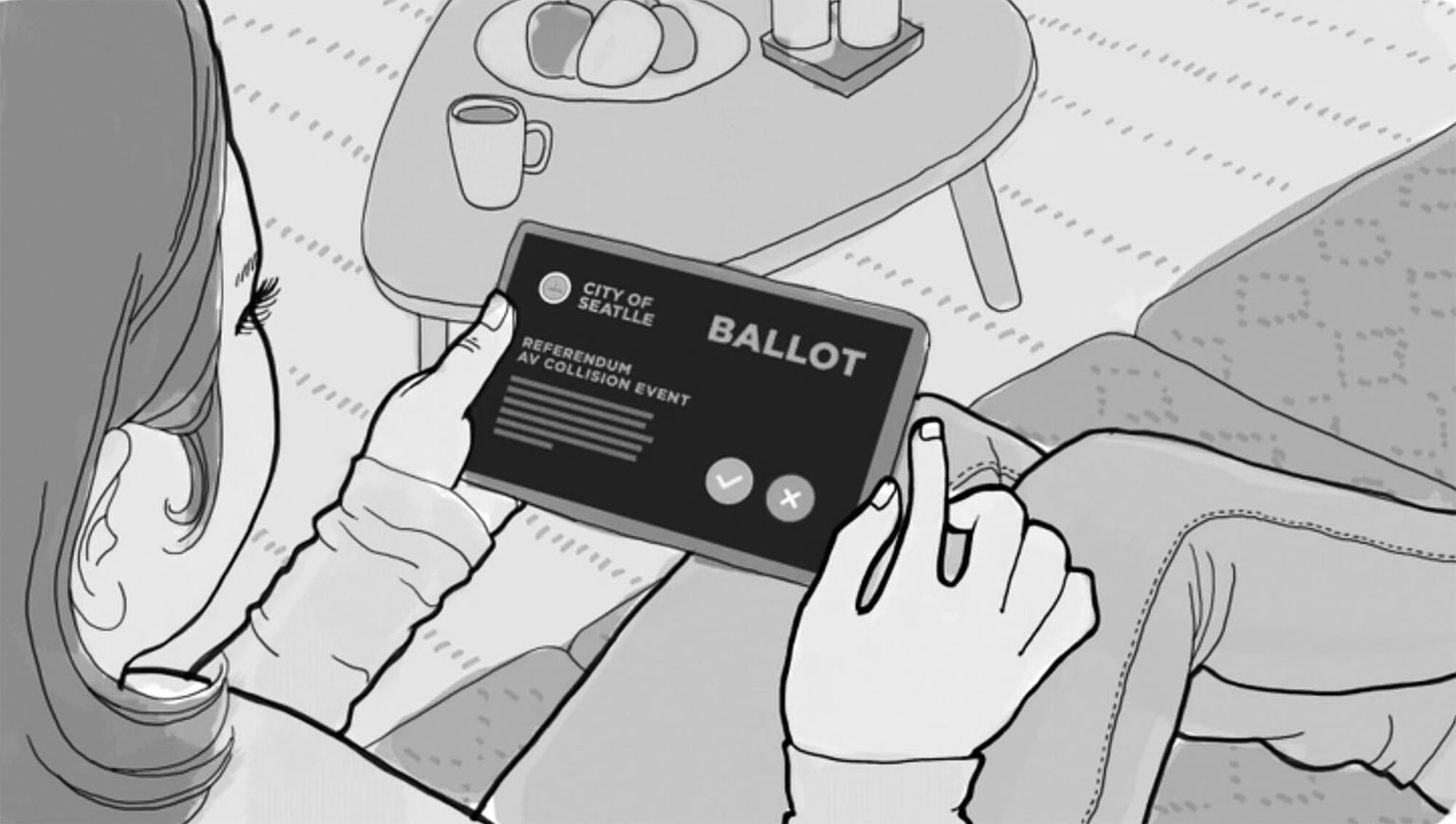

Most cities would admit that they were not well prepared for the emergence of Uber and Lyft several years ago; some are still struggling to figure out how those services fit into their city. So cities need to learn from those mistakes and start thinking rigorously about the futures they want from taxibot networks by answering these important questions about network and data ownership. If a city is slow or unwilling to answer these questions, industry will be happy to answer them for it.

This article was originally published in Fast Company magazine.